Introduction

Lately, I’ve been trying to understand how web apps can work offline and load faster, and that led me to service workers and caching. This post is a mix of notes, demos, and explanations , kind of like a study journal, but written to make it easy for others to follow too.

What is a Service Worker?

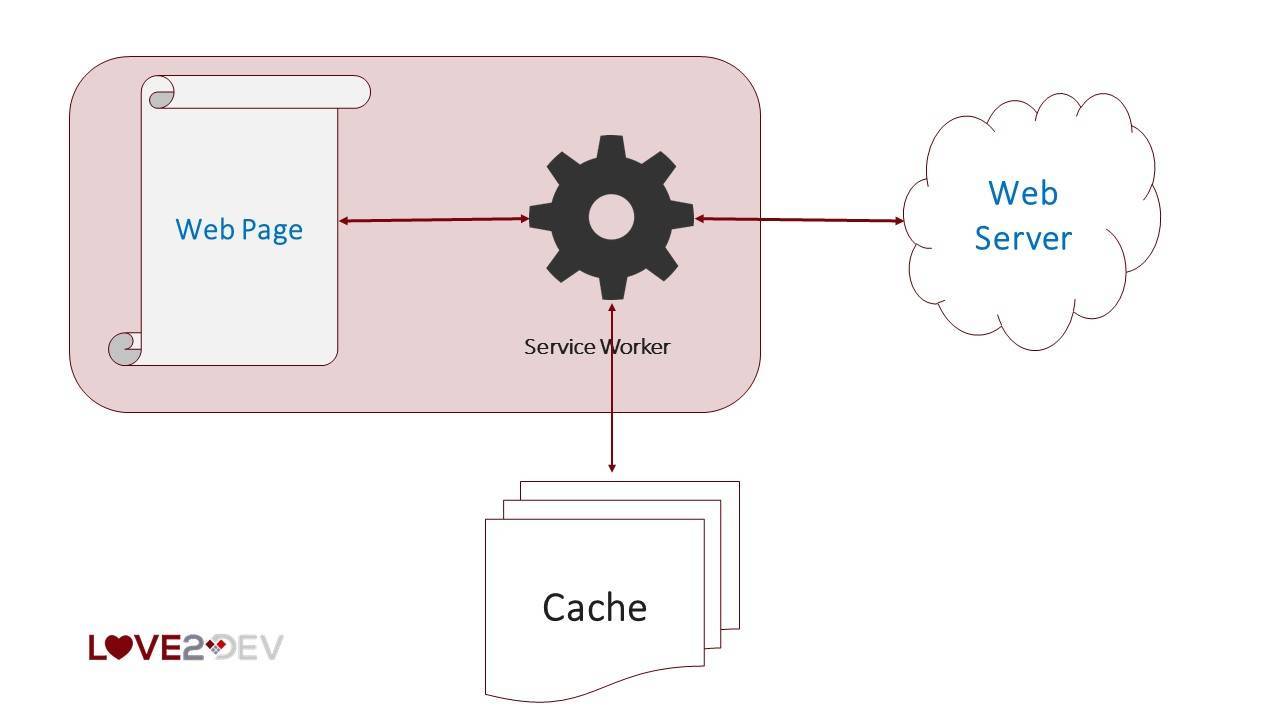

A service worker is a type of web worker that runs in the background, separate from the main browser thread. It basically acts like a network proxy . What makes it powerful is that it can intercept network requests, decide how to handle them, and even serve responses from a local cache if needed. This means it can help web apps work offline, load faster, and give users a smoother experience even when the network isn’t perfect.

To understand it better, here are some key aspects:

A service worker’s lifecycle

-

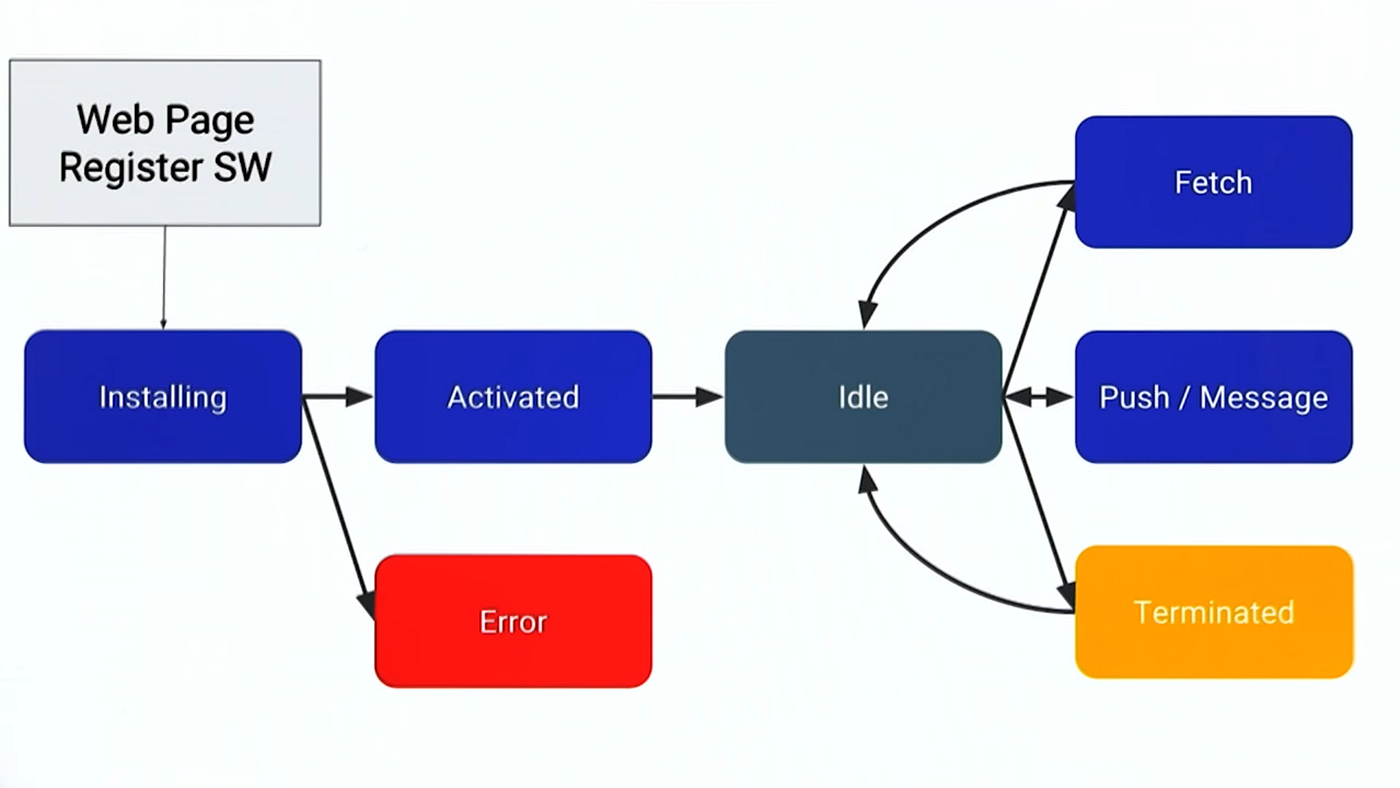

Registration - This is when the browser first becomes aware of the service worker. You typically do this in your main JavaScript file using

navigator.serviceWorker.register()method and give your service worker file as an argument .Here is an example

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) { window.addEventListener('load', () => { navigator.serviceWorker.register('/service-worker-file') .then(reg => console.log('Service Worker registered:', reg.scope)) .catch(err => console.error('Registration failed:', err)); }); } -

Installation - After registration, the install event is the first lifecycle event that the service worker receives. This is when the browser tries to install the service worker script for the first time (or when it detects a new version).

This phase is typically used to pre-cache static assets that the app needs to function offline. If the install step finishes successfully (i.e., event.waitUntil resolves without error), the service worker becomes eligible for activation.

self.addEventListener('install', (event) => { event.waitUntil( caches.open(CACHE_NAME).then((cache) => { return cache.addAll(STATIC_ASSETS); }) ); }); - Activation - Here, the new service worker takes control. It’s common to clean up old caches or outdated data at this point. This ensures users are getting the latest versions of your app’s assets.

self.addEventListener('activate', (event) => { caches.keys().then((cacheNames) => { cacheNames.forEach((name) => { if (name !== CACHE_NAME) { caches.delete(name); } }); }); }); - Update - Whenever the service worker file changes, the browser will attempt to update the old version. It will go through install and activate again if needed. You can also manually trigger updates via code.

- Idle / Event Listening -

Service workers don’t run forever ,they remain idle when not needed and wake up only to respond to events like

fetch,sync, orpush. This helps them be efficient and conserve resources.self.addEventListener('fetch', (event) => { const { request } = event; if (STATIC_ASSETS.includes(new URL(request.url).pathname)) { // Serve from cache event.respondWith( caches.match(request).then((cached) => cached || fetch(request)) ); } else { // use network event.respondWith(fetch(request)); } });

So now that we’ve seen how service workers install, activate, and intercept requests, let’s zoom in on one of the key reasons we use them in the first place: caching.

What is Cache Storage?

This is a built-in browser feature that gives your service worker a place to store network responses and frequently used assets , this could be a full HTML page, a stylesheet, or even data from an API.Everything inside is saved as a key-value pair,

- key - usually a request (like /index.html)

- value - the response returned from the network (like the actual content)

You are also in control of how you version and name your caches (like static-cache-v1). You can decide what is to be updated , what stays , and what is to be removed.

Let’s see this in action using the To-Do list app we just built.

Cache on Install

In the install event, we preload the static files our app needs to work offline

const CACHE_NAME = 'static-cache-v1';

const STATIC_ASSETS = [

'/',

'/index.html',

'/style.css',

'/script.js'

];

self.addEventListener('install', (event) => {

console.log('Installing and caching static assets...');

event.waitUntil(

caches.open(CACHE_NAME).then((cache) => {

return cache.addAll(STATIC_ASSETS);

})

);

self.skipWaiting(); // Makes SW activate immediately

});

Serve from Cache on Fetch

When a user navigates your app, the service worker intercepts every request and can serve it from the cache if it’s available.

self.addEventListener('fetch', (event) => {

const { request } = event;

if (STATIC_ASSETS.includes(new URL(request.url).pathname)) {

// Serve from cache first

event.respondWith(

caches.match(request).then((cached) => cached || fetch(request))

);

} else {

// use network

event.respondWith(fetch(request));

}

});

Why Do We Clone Requests and Responses?

If you’ve peeked into advanced service worker examples, you might’ve noticed something like response.clone() or request.clone(). But why is cloning even necessary?

In our earlier static caching example, cloning wasn’t needed ,as we were either serving from cache or fetching fresh content without saving it.

But things get more complex with dynamic caching. If you fetch a response and also want to save it to cache, you’ll need to clone it. Response objects are streams ,once consumed, they cannot be reused. Cloning lets you reuse them safely.

fetch(request).then(response => {

const copy = response.clone();

caches.open(CACHE_NAME).then(cache => cache.put(request, copy));

return response;

});

What’s Next?

So far, we’ve explored how service workers work, how they install, intercept network requests, and use cache storage to serve static assets. This is the foundation of offline-first web apps.

You can check out the code on GitHub.

But what happens when your app needs to cache things on the fly like API responses or newly requested pages? That’s where dynamic caching comes in.

In the next part of this series, we’ll explore:

- How to fetch and store responses during runtime

- When and why to clone requests/responses

- Cache strategies

- Cleaning up old or unnecessary cache entries

From here, service workers take on more responsibility in controlling how responses are fetched and stored.